From the Bahamas to Nigeria, China to Jamaica, a common theme unites countries that have rolled out their own CBDC: very few people actually use them.

Around the world, major economies are in an urgent race to launch their very own central bank digital currencies.

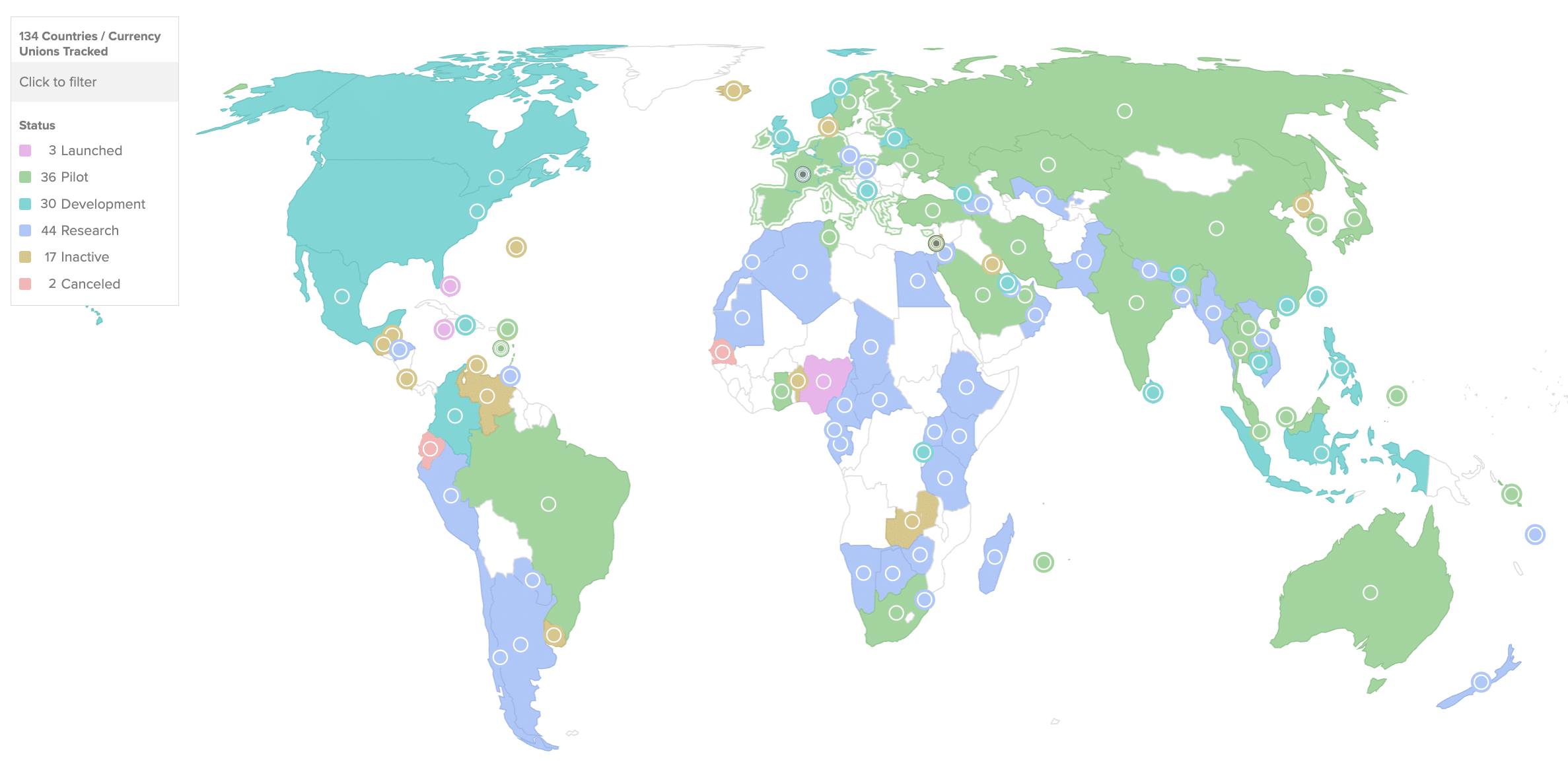

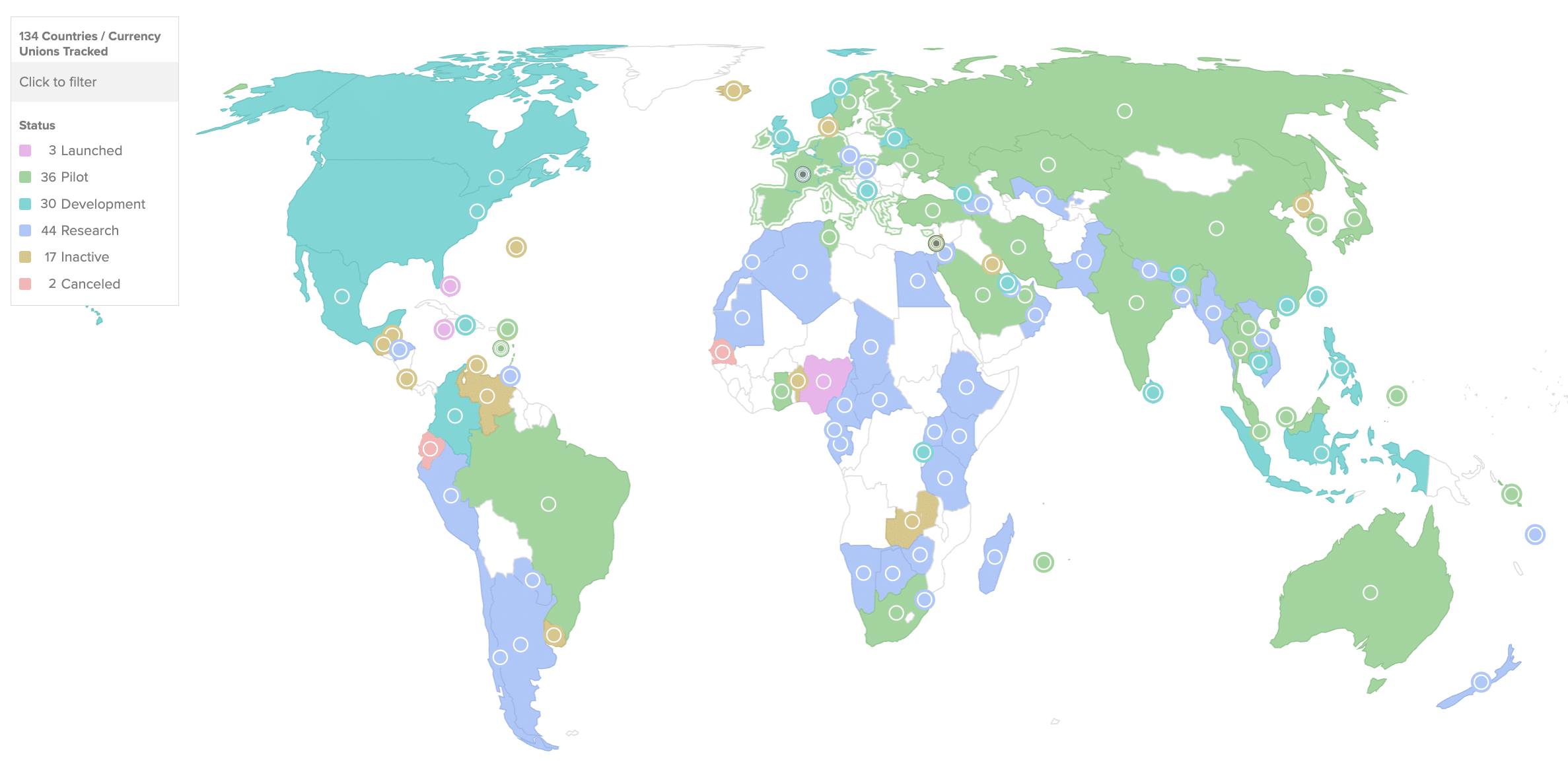

Data from the Atlantic Council suggests a staggering 134 countries around the world, representing 98% of global GDP, are now experimenting with one.

Of those, just three have launched so far, while 36 more are currently being put through their paces in pilot programs.

But despite the talk of faster cross-border transactions, reduced fees for businesses, and innovative new payment methods, there’s an uncomfortable truth for many nations who have invested countless millions into creating this infrastructure: demand has been pretty tepid.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City released a staggering report that examined how successful three retail CBDCs in the Caribbean had been since launch. It noted that none had managed to achieve widespread adoption among consumers.

It cited figures that show just 105,000 consumers and 1,500 merchants had embraced the Bahamian Sand Dollar by May 2023 — with the value of this CBDC representing a mere 0.19% of the total currency in circulation. Not good.

DCash, which spans the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union — as well as Jamaica’s JAM-DEX — have fared even worse, with a share of just 0.16% and 0.11% respectively.

On the other side of the world, in Asia, there have been similar teething troubles.

India has made much fanfare of the digital rupee — touting some of the main benefits as offline transactions in areas where there’s little internet access, along with programmable payments.

But a Reuters report recently revealed that, in the space of just six months, usage of this CBDC had plummeted precipitously to a mere tenth of the levels seen in December 2023. The sharp drop comes after incentives offered to early adopters came to an end.

Over in China, there was an especially embarrassing report when it emerged that government workers who were receiving their salaries in the digital yuan were swapping it for cash immediately.

Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund said adoption of Nigeria’s eNaira was “disappointingly low” in the 12 months after launch, with 98.5% of wallets going unused, meaning a “coordinated policy drive” was required to drum up interest.

Making CBDCs cool (again?)

There are a multitude of factors as to why central bank digital currencies are struggling to take off.

For one, there can often be a lack of awareness about what they are — and a technical divide facing older consumers who are more accustomed to physical cash.

And even among those who do know what a CBDC is, hurdles to adoption remain. A common criticism relates to how private these transactions are, and whether such digital assets can offer the same amount of anonymity as cash. Other sticking points include limits on the amount of CBDC that a single consumer can hold, while a lack of interest payments can be off putting too.

It’s also fair to say that commercial banks aren’t exactly thrilled by the rise of central bank digital currencies, amid fears that they have the potential to undermine their business models.

For CBDCs to actually have a chance at gaining traction, they need to offer clear and compelling benefits — including perks that existing payment methods cannot match. Given how the likes of China are home to vast super-apps that blend everything from messaging to grocery shopping in one place, that’s easier said than done.

Some countries are now putting their foot down and are planning to introduce regulations that will effectively mandate the use of CBDCs. For example, the Bahamas is working on new rules that will force central banks to offer access to the Sand Dollar, in what’s been likened to a “carrot and stick” approach. Success here could influence what other economies do in the future.

You’ll be unsurprised to hear that crypto enthusiasts are rubbing their hands with glee when they hear about the resistance that CBDCs have suffered so far, along with a lack of momentum when it comes to uptake.

And with major economies such as the U.K., U.S. and EU still many years away from having a central bank digital currency of their own — with no guarantees one will ever debut — there’s a real chance some regions will abandon this policy altogether.

From the Bahamas to Nigeria, China to Jamaica, a common theme unites countries that have rolled out their own CBDC: very few people actually use them.

Around the world, major economies are in an urgent race to launch their very own central bank digital currencies.

Data from the Atlantic Council suggests a staggering 134 countries around the world, representing 98% of global GDP, are now experimenting with one.

Of those, just three have launched so far, while 36 more are currently being put through their paces in pilot programs.

But despite the talk of faster cross-border transactions, reduced fees for businesses, and innovative new payment methods, there’s an uncomfortable truth for many nations who have invested countless millions into creating this infrastructure: demand has been pretty tepid.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City released a staggering report that examined how successful three retail CBDCs in the Caribbean had been since launch. It noted that none had managed to achieve widespread adoption among consumers.

It cited figures that show just 105,000 consumers and 1,500 merchants had embraced the Bahamian Sand Dollar by May 2023 — with the value of this CBDC representing a mere 0.19% of the total currency in circulation. Not good.

DCash, which spans the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union — as well as Jamaica’s JAM-DEX — have fared even worse, with a share of just 0.16% and 0.11% respectively.

On the other side of the world, in Asia, there have been similar teething troubles.

India has made much fanfare of the digital rupee — touting some of the main benefits as offline transactions in areas where there’s little internet access, along with programmable payments.

But a Reuters report recently revealed that, in the space of just six months, usage of this CBDC had plummeted precipitously to a mere tenth of the levels seen in December 2023. The sharp drop comes after incentives offered to early adopters came to an end.

Over in China, there was an especially embarrassing report when it emerged that government workers who were receiving their salaries in the digital yuan were swapping it for cash immediately.

Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund said adoption of Nigeria’s eNaira was “disappointingly low” in the 12 months after launch, with 98.5% of wallets going unused, meaning a “coordinated policy drive” was required to drum up interest.

Making CBDCs cool (again?)

There are a multitude of factors as to why central bank digital currencies are struggling to take off.

For one, there can often be a lack of awareness about what they are — and a technical divide facing older consumers who are more accustomed to physical cash.

And even among those who do know what a CBDC is, hurdles to adoption remain. A common criticism relates to how private these transactions are, and whether such digital assets can offer the same amount of anonymity as cash. Other sticking points include limits on the amount of CBDC that a single consumer can hold, while a lack of interest payments can be off putting too.

It’s also fair to say that commercial banks aren’t exactly thrilled by the rise of central bank digital currencies, amid fears that they have the potential to undermine their business models.

For CBDCs to actually have a chance at gaining traction, they need to offer clear and compelling benefits — including perks that existing payment methods cannot match. Given how the likes of China are home to vast super-apps that blend everything from messaging to grocery shopping in one place, that’s easier said than done.

Some countries are now putting their foot down and are planning to introduce regulations that will effectively mandate the use of CBDCs. For example, the Bahamas is working on new rules that will force central banks to offer access to the Sand Dollar, in what’s been likened to a “carrot and stick” approach. Success here could influence what other economies do in the future.

You’ll be unsurprised to hear that crypto enthusiasts are rubbing their hands with glee when they hear about the resistance that CBDCs have suffered so far, along with a lack of momentum when it comes to uptake.

And with major economies such as the U.K., U.S. and EU still many years away from having a central bank digital currency of their own — with no guarantees one will ever debut — there’s a real chance some regions will abandon this policy altogether.